40. Construcción de Geometrías¶

La capa nyc_subway_stations nos ha proporcionado muchos ejemplos interesantes, pero hay algo que llama la atención:

Aunque es una base de datos de todas las estaciones, ¡no permite visualizar fácilmente las rutas! En este capítulo utilizaremos funciones avanzadas de PostgreSQL y PostGIS para construir una nueva capa de rutas lineales a partir de la capa de puntos de las estaciones de metro.

Dos cuestiones dificultan nuestra tarea:

La columna

routesdenyc_subway_stationstiene varios identificadores de ruta en cada fila, por lo que una estación que podría aparecer en varias rutas sólo aparece una vez en la tabla.En relación con el problema anterior, no hay información sobre el orden de las rutas en la tabla de estaciones, por lo que, aunque es posible encontrar todas las estaciones de una ruta determinada, no es posible utilizar los atributos para determinar el orden en que los trenes pasan por las estaciones.

El segundo problema es el más difícil: dado un conjunto desordenado de puntos de una ruta, ¿cómo los ordenamos para que coincidan con la ruta real?.

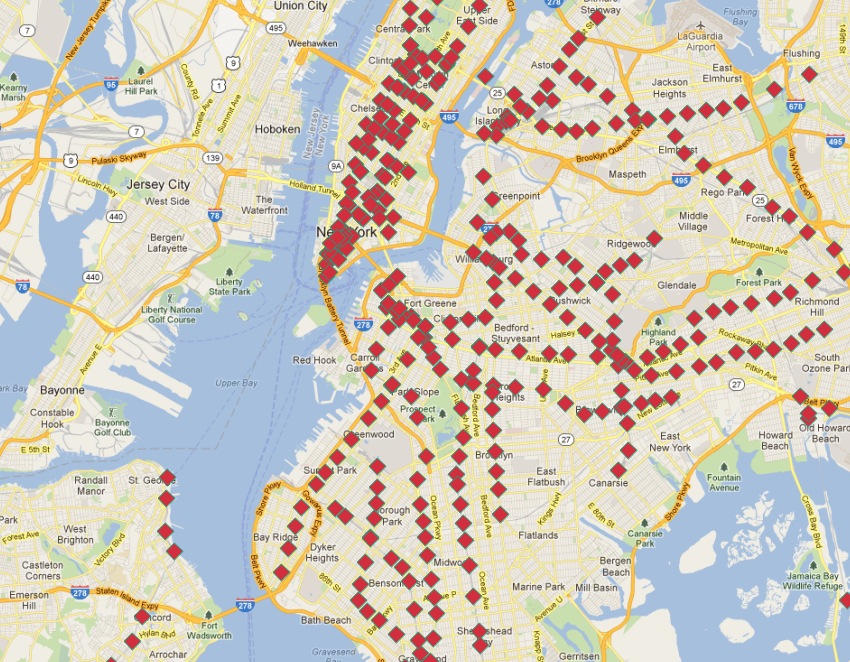

Estas son las paradas del tren «Q»:

SELECT s.gid, s.geom

FROM nyc_subway_stations s

WHERE (strpos(s.routes, 'Q') <> 0);

En esta imagen, las paradas están etiquetadas con su clave primaria gid.

Si empezamos en una de las estaciones finales, la siguiente estación de la línea parece ser siempre la más cercana. Podemos repetir el proceso cada vez siempre que excluyamos de nuestra búsqueda todas las estaciones encontradas anteriormente.

Hay dos formas de ejecutar una rutina iterativa de este tipo en una base de datos:

Utilizando un lenguaje procedimental, como PL/PgSQL.

Uso recursivo de expresiones comunes.

Las expresiones comunes de tabla (CTE) tienen la virtud de no requerir una definición de función para ejecutarse. Aquí está la CTE para calcular la línea de ruta del tren “Q”, empezando por la parada más al norte (donde gid es 304).

WITH RECURSIVE next_stop(geom, idlist) AS (

(SELECT

geom,

ARRAY[gid] AS idlist

FROM nyc_subway_stations

WHERE gid = 304)

UNION ALL

(SELECT

s.geom,

array_append(n.idlist, s.gid) AS idlist

FROM nyc_subway_stations s, next_stop n

WHERE strpos(s.routes, 'Q') != 0

AND NOT n.idlist @> ARRAY[s.gid]

ORDER BY ST_Distance(n.geom, s.geom) ASC

LIMIT 1)

)

SELECT geom, idlist FROM next_stop;

El CTE consta de dos partes unidas entre sí:

La primera parte establece un punto de inicio para la expresión. Obtenemos la geometría inicial e inicializamos la matriz de identificadores visitados, utilizando el registro de «gid» 304 (el final de la línea).

La segunda parte itera hasta que no encuentra más registros. En cada iteración toma el valor devuelto de la iteración anterior a través de la autorreferencia a «next_stop». Buscamos en cada parada de la línea Q (strpos(s.rutas,”Q”)) que no hayamos añadido ya a nuestra lista de visitadas (NOT n.idlist @> ARRAY[s.gid]) y las ordenamos por su distancia al punto anterior, tomando sólo la primera (la más cercana).

Más allá de la propia CTE recursiva, hay una serie de características avanzadas de PostgreSQL que se utilizan aquí:

¡Estamos usando ARRAY! PostgreSQL soporta arreglos de cualquier tipo. En este caso tenemos un arreglo de enteros, pero también podríamos construir un arreglo de geometrías, o cualquier otro tipo de PostgreSQL.

Estamos utilizando array_append para construir nuestro vector de identificadores de estación visitados.

Estamos utilizando el operador de matrices @> («array contains») para averiguar cuál de las estaciones de tren Q ya hemos visitado. El operador @> requiere valores ARRAY en ambos lados, por lo que tenemos que convertir los números «gid» individuales en arrays con un solo elemento utilizando la sintaxis ARRAY[].

Al ejecutar la consulta, se obtiene cada geometría en el orden en que se encuentra (que es el orden de ruta), así como la lista de identificadores ya visitados. Envolver las geometrías en la función agregada ST_MakeLine de PostGIS convierte el conjunto de geometrías en una única línea, construida en el orden proporcionado.

WITH RECURSIVE next_stop(geom, idlist) AS (

(SELECT

geom,

ARRAY[gid] AS idlist

FROM nyc_subway_stations

WHERE gid = 304)

UNION ALL

(SELECT

s.geom,

array_append(n.idlist, s.gid) AS idlist

FROM nyc_subway_stations s, next_stop n

WHERE strpos(s.routes, 'Q') != 0

AND NOT n.idlist @> ARRAY[s.gid]

ORDER BY ST_Distance(n.geom, s.geom) ASC

LIMIT 1)

)

SELECT ST_MakeLine(geom) AS geom FROM next_stop;

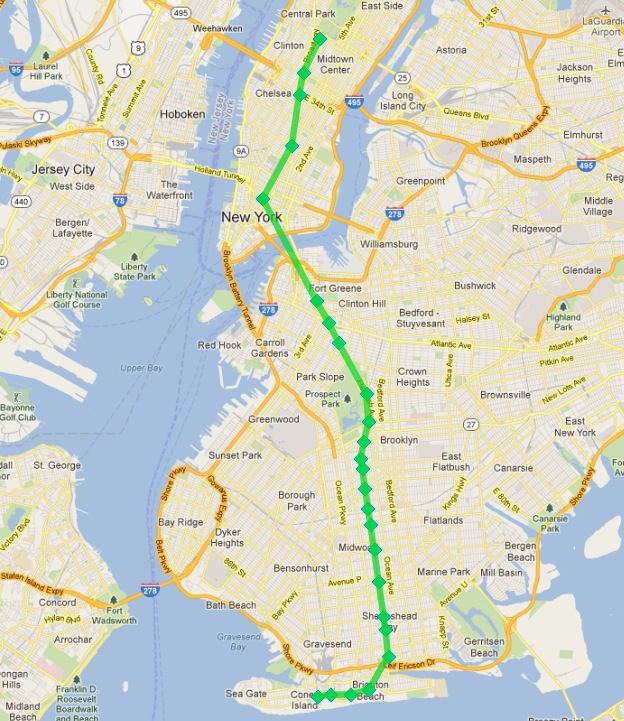

La cual luce como:

Éxito!

Excepto por dos problemas:

Aquí sólo estamos calculando una ruta de metro, queremos calcular todas las rutas.

Nuestra consulta requiere un conocimiento a priori, el identificador inicial de la estación que sirve de semilla para el algoritmo de búsqueda que construye la ruta.

Abordemos primero el problema más difícil: averiguar cuál es la primera estación de una ruta sin echar un vistazo manual al conjunto de estaciones que la componen.

Nuestras paradas del tren «Q» pueden servir de punto de partida. ¿Qué caracteriza a las estaciones finales de la ruta?

Una respuesta es «son las estaciones más al norte (septentrionales) y más al sur ( meridionales)». Sin embargo, imagine que el tren «Q» circulara de este a oeste. ¿Se cumpliría la condición?

Una caracterización menos direccional de las estaciones finales es «son las estaciones más alejadas del centro de la ruta». Con esta caracterización no importa si la ruta discurre en dirección norte/sur o este/oeste, sólo que discurra más o menos en una dirección, sobre todo en los extremos.

Puesto que no existe una heurística al 100% para averiguar los puntos finales, probemos esta segunda regla.

Nota

Un fallo obvio de la regla «lo más lejos posible del centro» es una línea circular, como la Circle Line de Londres (Reino Unido). Afortunadamente, Nueva York no tiene líneas de este tipo!

Para determinar las estaciones finales de cada ruta, primero tenemos que averiguar qué rutas existen. Encontramos las rutas distintas.

WITH routes AS (

SELECT DISTINCT unnest(string_to_array(routes,',')) AS route

FROM nyc_subway_stations ORDER BY route

)

SELECT * FROM routes;

Observa el uso de dos funciones avanzadas de PostgreSQL para ARRAYS:

string_to_array recibe una cadena y la divide en un arreglo usando un carácter separador. PostgreSQL soporta arreglos de cualquier tipo, por lo que es posible construir arreglos de cadenas, como en este caso, pero también de geometrías y geographies como veremos más adelante en este ejemplo.

unnest recibe un arreglo y construye una nueva fila para cada entrada del arreglo. El efecto es tomar un arreglo «horizontal» incrustado en una sola fila y convertirlo en un arreglo «vertical» con una fila por cada valor.

El resultado es una lista de todos los identificadores únicos de rutas de metro.

route

-------

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

J

L

M

N

Q

R

S

V

W

Z

(24 rows)

Podemos ampliar este resultado uniéndolo nuevamente a la tabla nyc_subway_stations para crear una nueva tabla que tenga, para cada ruta, una fila por cada estación en esa ruta.

WITH routes AS (

SELECT DISTINCT unnest(string_to_array(routes,',')) AS route

FROM nyc_subway_stations ORDER BY route

),

stops AS (

SELECT s.gid, s.geom, r.route

FROM routes r

JOIN nyc_subway_stations s

ON (strpos(s.routes, r.route) <> 0)

)

SELECT * FROM stops;

gid | geom | route

-----+----------------------------------------------------+-------

2 | 010100002026690000CBE327F938CD21415EDBE1572D315141 | 1

3 | 010100002026690000C676635D10CD2141A0ECDB6975305141 | 1

20 | 010100002026690000AE59A3F82C132241D835BA14D1435141 | 1

22 | 0101000020266900003495A303D615224116DA56527D445141 | 1

...etc...

Ahora podemos encontrar el punto central reuniendo todas las estaciones de cada ruta en un único multi-punto y calculando el centroide de ese multi-punto.

WITH routes AS (

SELECT DISTINCT unnest(string_to_array(routes,',')) AS route

FROM nyc_subway_stations ORDER BY route

),

stops AS (

SELECT s.gid, s.geom, r.route

FROM routes r

JOIN nyc_subway_stations s

ON (strpos(s.routes, r.route) <> 0)

),

centers AS (

SELECT ST_Centroid(ST_Collect(geom)) AS geom, route

FROM stops

GROUP BY route

)

SELECT * FROM centers;

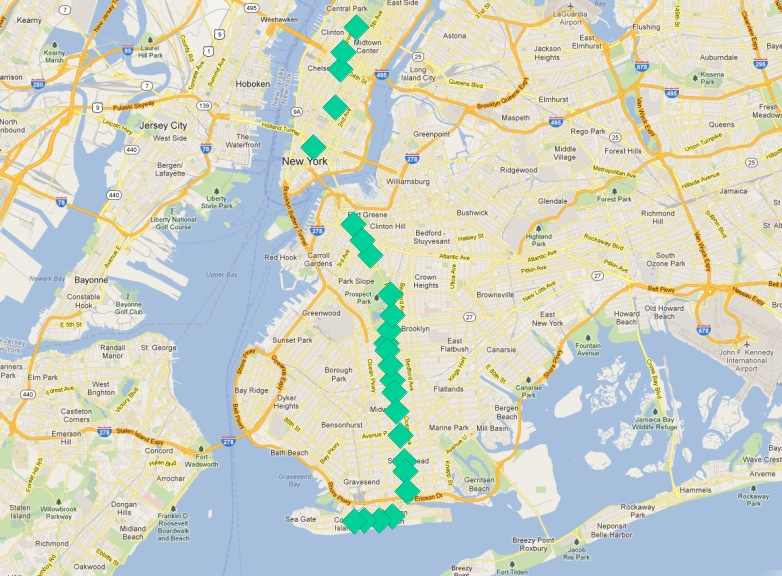

El punto central de la colección de paradas del tren “Q” se ve así:

Entonces, la parada más al norte, el punto final, parece ser también la parada más alejada del centro. Vamos a calcular el punto más lejano para cada ruta.

WITH routes AS (

SELECT DISTINCT unnest(string_to_array(routes,',')) AS route

FROM nyc_subway_stations ORDER BY route

),

stops AS (

SELECT s.gid, s.geom, r.route

FROM routes r

JOIN nyc_subway_stations s

ON (strpos(s.routes, r.route) <> 0)

),

centers AS (

SELECT ST_Centroid(ST_Collect(geom)) AS geom, route

FROM stops

GROUP BY route

),

stops_distance AS (

SELECT s.*, ST_Distance(s.geom, c.geom) AS distance

FROM stops s JOIN centers c

ON (s.route = c.route)

ORDER BY route, distance DESC

),

first_stops AS (

SELECT DISTINCT ON (route) stops_distance.*

FROM stops_distance

)

SELECT * FROM first_stops;

Hemos agregado dos subconsultas esta vez:

stops_distance une los puntos centrales nuevamente a la tabla de estaciones y calcula la distancia entre las estaciones y el centro para cada ruta. El resultado se ordena de tal manera que los registros salen en lotes para cada ruta, con la estación más lejana como el primer registro del lote.

first_stops filtra la salida de stops_distance tomando solo el primer registro de cada grupo distinto. Debido a la forma en que ordenamos stops_distance, el primer registro es el más lejano, lo que significa que es la estación que queremos usar como semilla inicial para construir cada ruta del metro.

Ahora sabemos cada ruta y sabemos (aproximadamente) desde qué estación comienza cada ruta: estamos listos para generar las líneas de ruta!

Pero primero, necesitamos convertir nuestra expresión CTE recursiva en una función que podamos llamar con parámetros.

CREATE OR REPLACE function walk_subway(integer, text) returns geometry AS

$$

WITH RECURSIVE next_stop(geom, idlist) AS (

(SELECT

geom AS geom,

ARRAY[gid] AS idlist

FROM nyc_subway_stations

WHERE gid = $1)

UNION ALL

(SELECT

s.geom AS geom,

array_append(n.idlist, s.gid) AS idlist

FROM nyc_subway_stations s, next_stop n

WHERE strpos(s.routes, $2) != 0

AND NOT n.idlist @> ARRAY[s.gid]

ORDER BY ST_Distance(n.geom, s.geom) ASC

LIMIT 1)

)

SELECT ST_MakeLine(geom) AS geom

FROM next_stop;

$$

language 'sql';

Y ahora estamos listos para empezar!

CREATE TABLE nyc_subway_lines AS

-- Distinct route identifiers!

WITH routes AS (

SELECT DISTINCT unnest(string_to_array(routes,',')) AS route

FROM nyc_subway_stations ORDER BY route

),

-- Joined back to stops! Every route has all its stops!

stops AS (

SELECT s.gid, s.geom, r.route

FROM routes r

JOIN nyc_subway_stations s

ON (strpos(s.routes, r.route) <> 0)

),

-- Collects stops by routes and calculate centroid!

centers AS (

SELECT ST_Centroid(ST_Collect(geom)) AS geom, route

FROM stops

GROUP BY route

),

-- Calculate stop/center distance for each stop in each route.

stops_distance AS (

SELECT s.*, ST_Distance(s.geom, c.geom) AS distance

FROM stops s JOIN centers c

ON (s.route = c.route)

ORDER BY route, distance DESC

),

-- Filter out just the furthest stop/center pairs.

first_stops AS (

SELECT DISTINCT ON (route) stops_distance.*

FROM stops_distance

)

-- Pass the route/stop information into the linear route generation function!

SELECT

ascii(route) AS gid, -- QGIS likes numeric primary keys

route,

walk_subway(gid, route) AS geom

FROM first_stops;

-- Do some housekeeping too

ALTER TABLE nyc_subway_lines ADD PRIMARY KEY (gid);

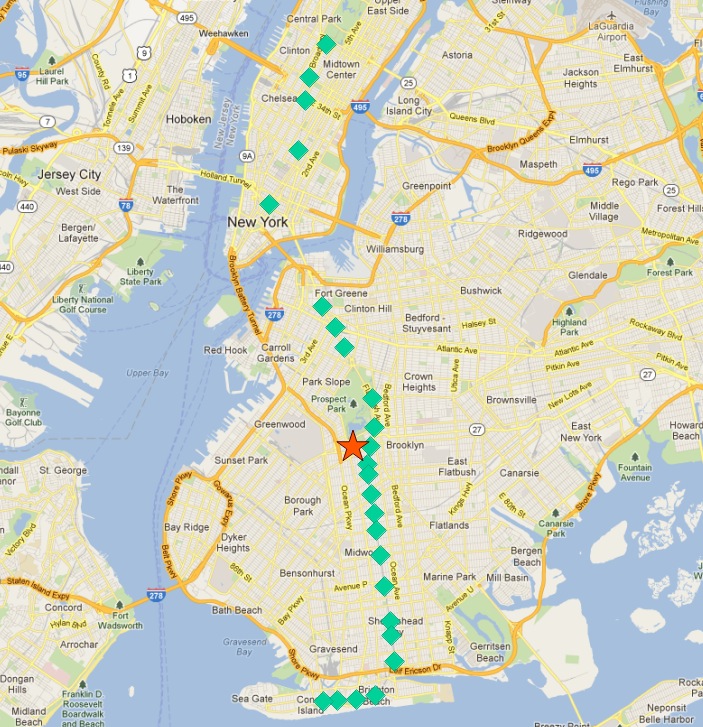

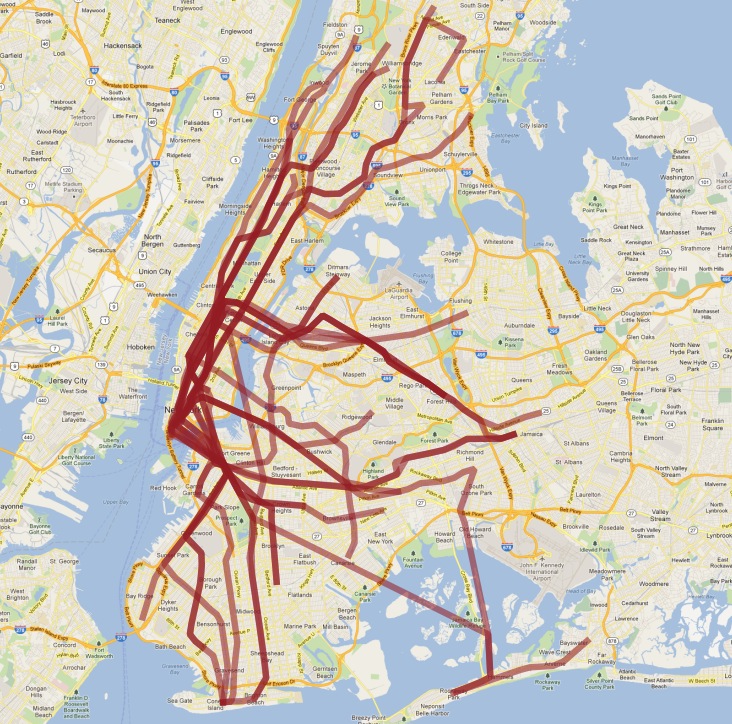

Así es como se ve nuestra tabla final visualizada en QGIS:

Como de costumbre, hay algunos problemas con nuestra comprensión simple de los datos:

en realidad hay dos trenes “S” (shuttle de corta distancia), uno en Manhattan y otro en Rockaways, y los unimos porque ambos se llaman “S”;

el tren “4” (y algunos otros) se divide al final de una línea en dos terminales, por lo que el supuesto de «seguir una línea» se rompe y el resultado tiene un gancho extraño al final.

Esperamos que este ejemplo haya proporcionado una idea de algunas de las manipulaciones de datos complejas que son posibles combinando las características avanzadas de PostgreSQL y PostGIS.